“the idea of the lone woman who shuns the conventions of her era and dedicates herself like a kind

of

patchbay-nun to uncovering the mysteries of sound is an appealing one that plays easily into the

fetishization of outsider figures”.

“Inheritance can be understood as both bodily and historical; we inherit chat we receive as the

condition of our

arrival into the world, as an arrival that leaves and makes an impression. (...) If history is made

‘out of’

what is passed down, as the conditions in which we live, then history is made

out of what is given not only in the sense of that which is ‘always already’ there, before our own

arrival,

but in the active sense of the gift: history is a gift given that, when given is received.”

- Sara Ahmed, “Queer Phenomenology”, 2006

While archives are being rediscovered, discussions about gender representation and equality are

globally

gaining power in society in general. Therefore, we are discovering a lot more about the

contribution of

minorities in technology and music as some researchers open archives and investigate. Those

discussions

also brought more light on musicians and DJs from the FLINTA*

community in the

industry. According to

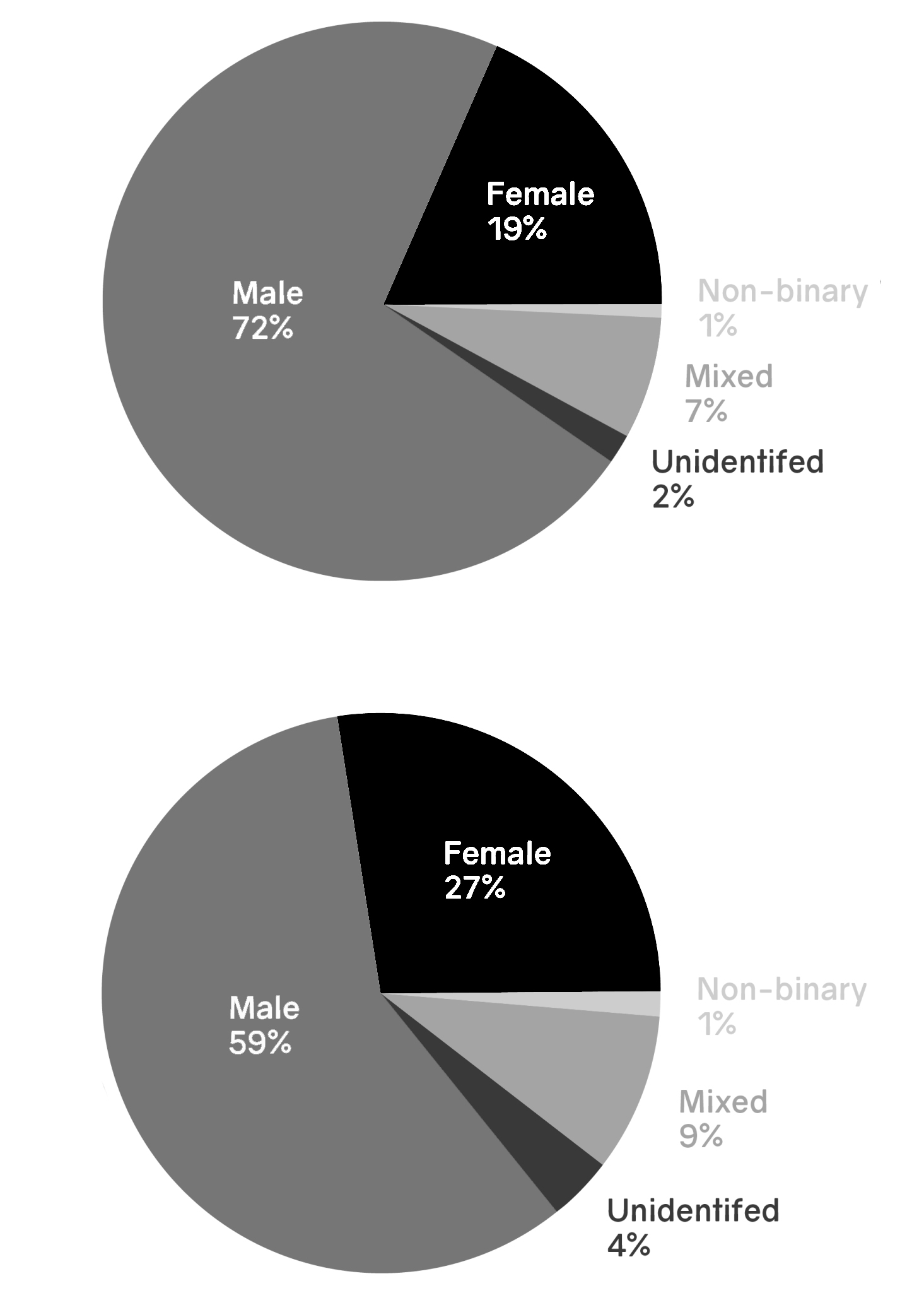

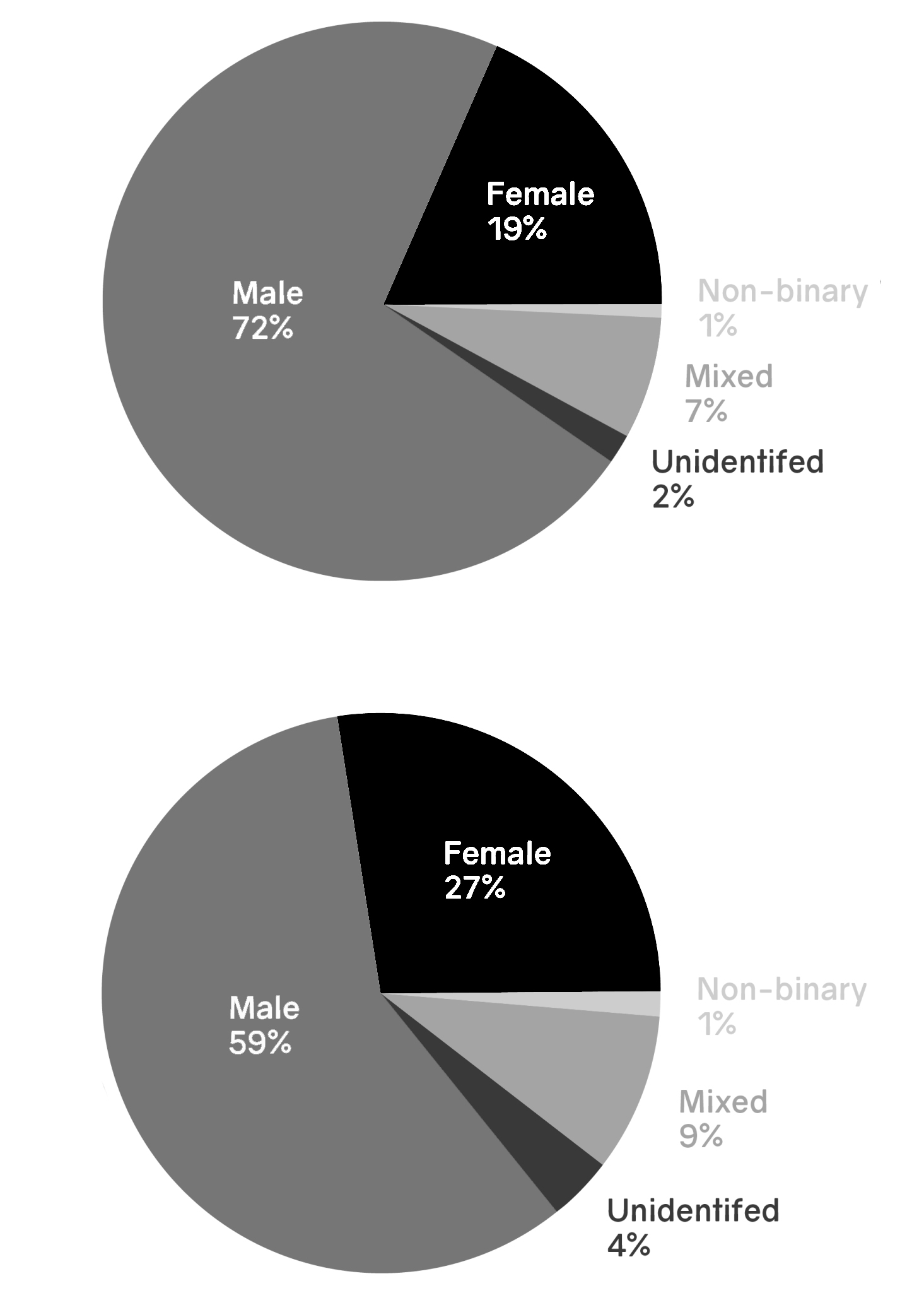

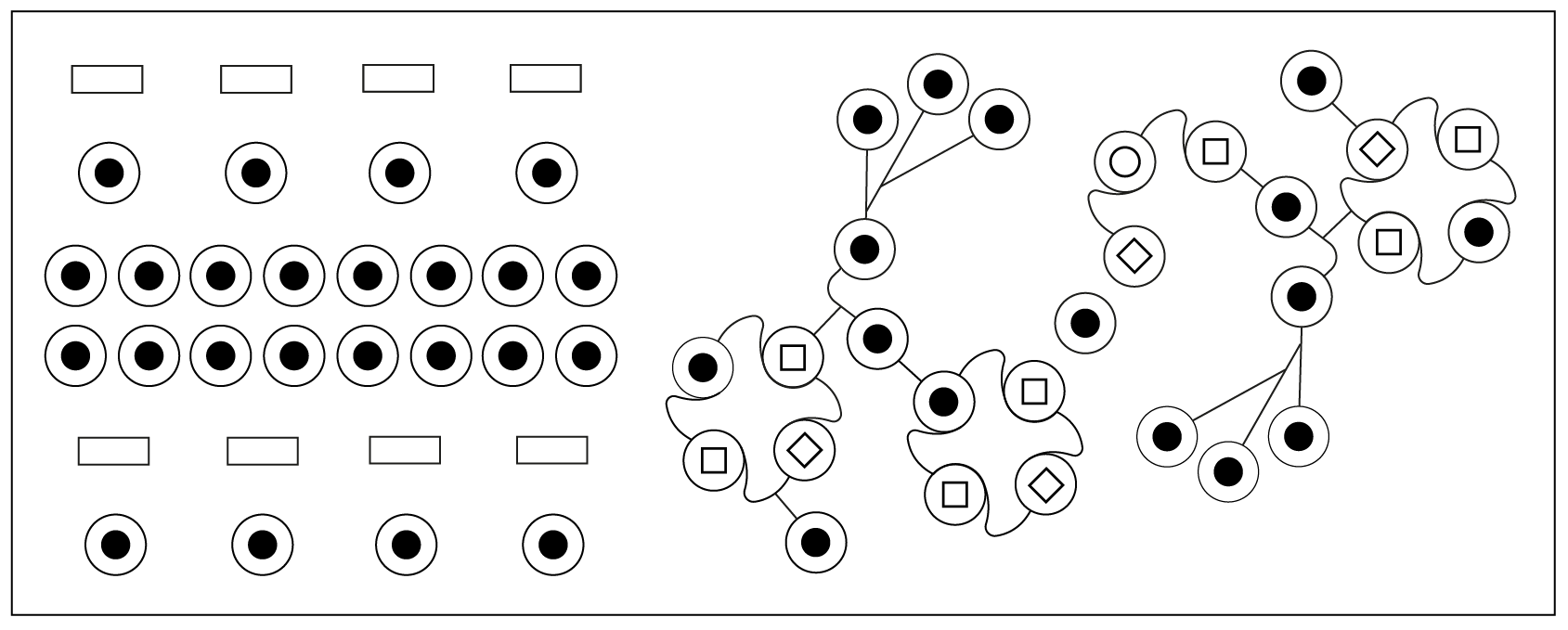

the female:pressure FACTS survey 2022:

“FACTS 2022 reveals a rise in the proportion of female acts from 9.2% in 2012 to 26.9% in

2020–2021. The

data on non-binary artists shows an increase from 0.4% to 1.3% from 2017 to 2021. (…) However,

with female

and non-binary acts comprising only a little over a quarter of all artists booked, there is

still a

significant imbalance in gender representation on electronic music festival stages today.”

Even though the gender representation in the music field is getting better,but one cannot

say the same

for the rest of the music sphere.

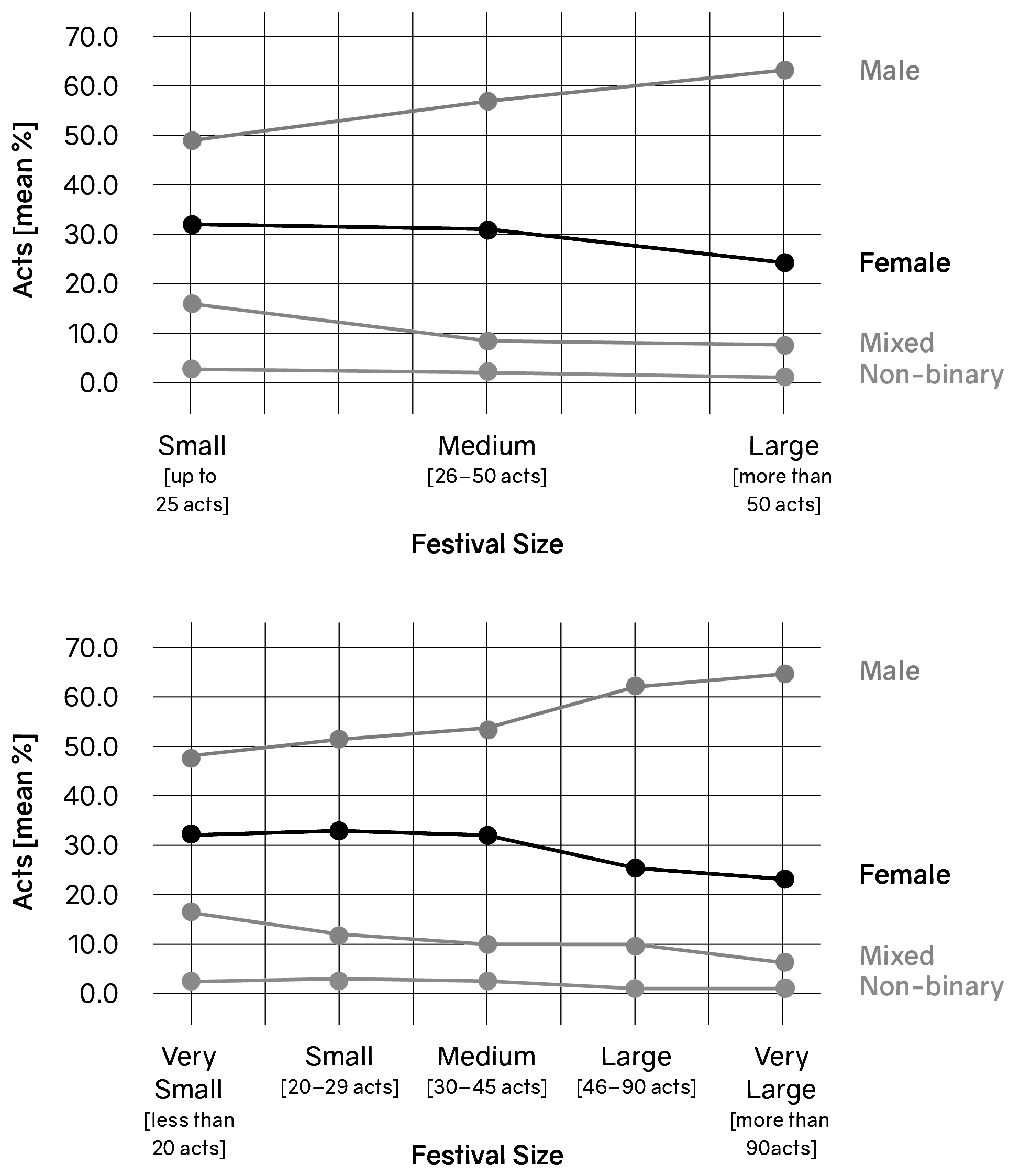

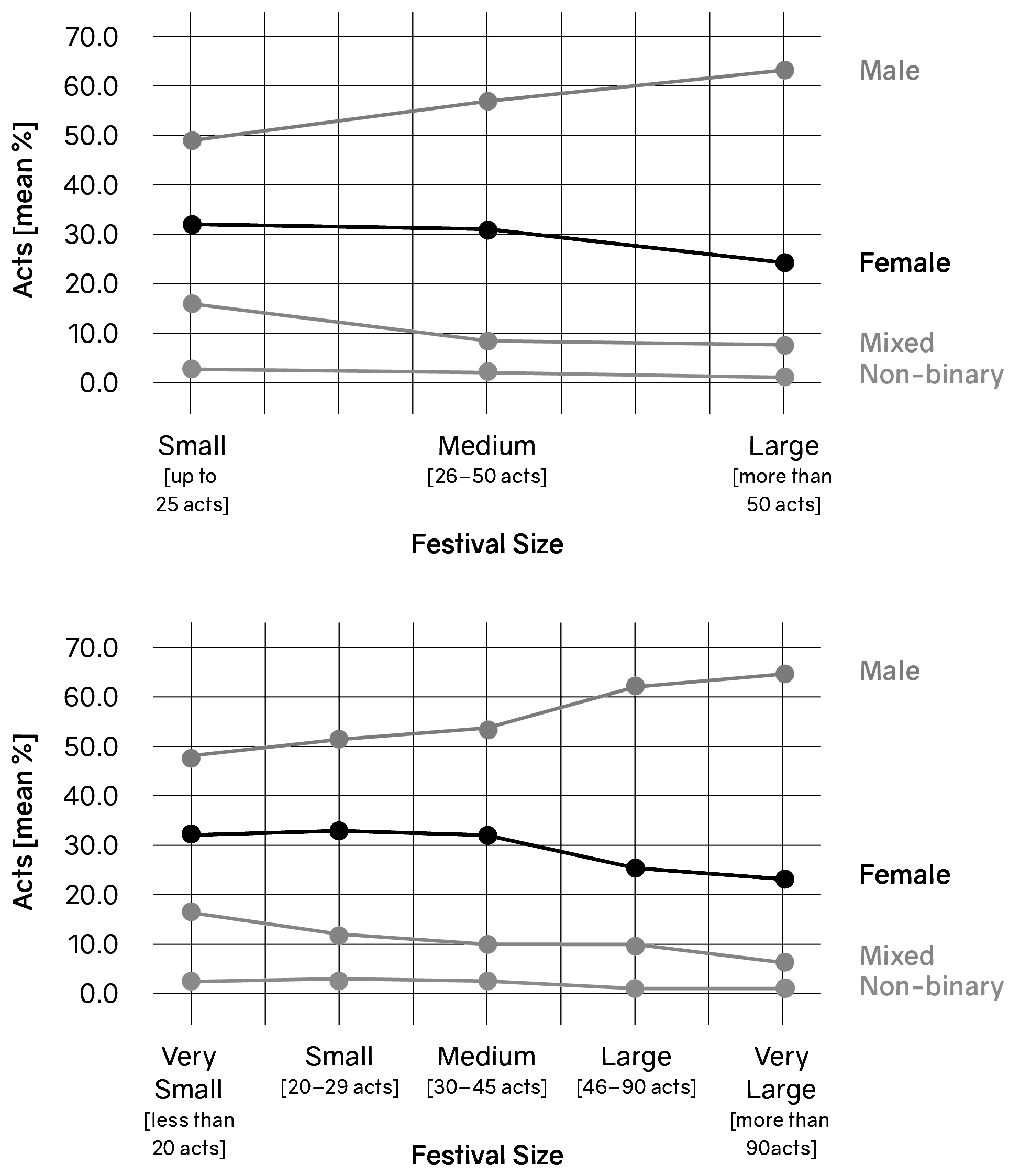

This is well corroborated by those statistics for female:pressure FACTS survey, presenting

gender

representation in regard to the size of the festivals.

Nevertheless, I still hear some worrying anecdotes from my fellow FLINTA*

producers or DJs. A

friend of mine told me recently that after performing a DJ set in C12, a famous club in

Brussels

focusing on electronic music, a guy came to her explaining her how to perform a DJ set

composed of dance

music. You could argue that C12 is not exactly an alternative venue, that the public is

mixed and thus

such things can happen more easily. I would argue that it is still a shame not to be able to

perform

wherever you want without receiving such comments.

To the question “Do you sometimes think about your place as female gendered artists within

the music

scene?” crysoma replies:

Solène: I think that each time we played it was a super present thing. For example in how we

are

welcomed

or in the way others perceive what we do. Or for example during feedback around our

performances. People

put

you in your girl's place by saying for example: “It's good for girls to do sounds like that.

Maëva: Or “Seeing girls making loud noise music is not usual!”.

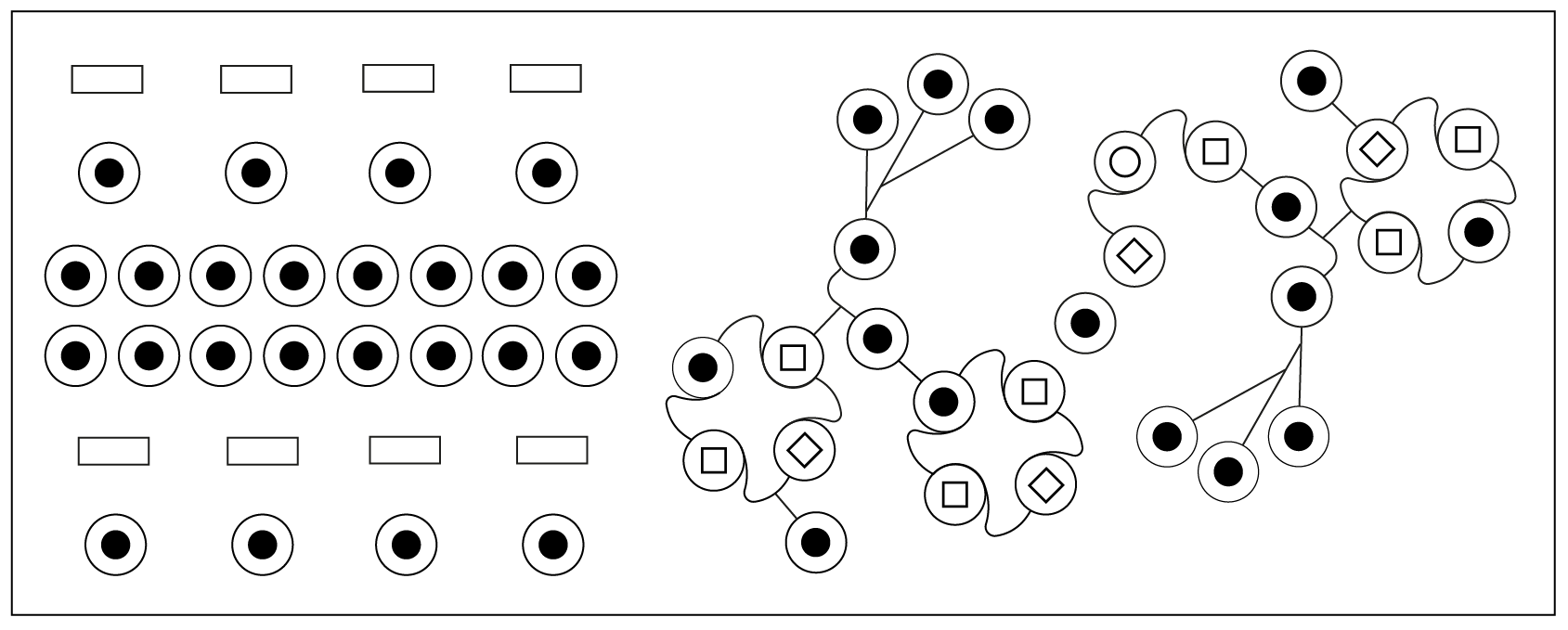

female:pressure FACTS survey 2022,

Gender proportions of festival acts

[Above: 2012 to 2021. Below: 2020 to 2021]

female:pressure FACTS survey 2022,

Female, male, non-binary and mixed acts by festival size in three [above] and five

[below]

categories

[2020 to 2021]

Their answer shows that stigmas are still present, even more so if you are a

female-identifying artist

playing harsh music. Part of why they began making music together was a response to the lack

of gender

representation in the events of their school:

Solène: There are several events per year in our school such as workshop weeks. They often end

with a music

event or a party. Martha, one of the teachers, was pissed that the people showing up for

performances were

always guys and that no one questioned it. There is a boy in my class who’s a DJ playing in a

lot of venues

and it was every time he and his friends who performed. Martha couldn't stand it so she asked us

if we knew

other people making music and she even asked us "Why wouldn’t you make music then?” So we did.

Some of the interviewees also felt that some people were quite discouraging towards them. Or

that they

feel

like there is still an overall confidence that cis gendered male foster more easily early on

in their

practice. To the question “Do you think your gender had any kind of influence on your music

or the way

that

your perceived as a performer?”, Luisa Mei and Maëva from crysoma answer:

Luisa Mei: Probably it does. When I first started learning a lot of people discouraged me:

“SuperCollider is

so hard. It’s going to be difficult, you’re going to want to drop out of the class” whatever.

But that made

me actually more willing to succeed (laughs). And I proved them wrong. I can use SuperCollider,

it's not

that hard. I think getting there people were kind of doubting me. Not in a mean way, kind of

joking but

still. But now as a performer I don’t feel there’s too many barriers for me to do what I want.

Maëva: When I look around me, most of the guys we know who make noise or set up collectives,

they play

together directly like “we already have a practice, we're here”. While we really did not feel

legitimate to

promote ourselves or anything. We don't introduce ourselves by saying “I make music”. Now we do

so a lot

more because we understand that we are actually really doing something. For guys who have been

making music

for a shorter time than us, it's almost obvious for them that they have a practice and they're

going to

promote themselves directly to people for concerts or something.

The Second Sound – Conversations on Gender and Music (2020), a

book displaying a survey

made by Julia Eckhardt and

Leen De Graeve, brings together anonymous testimonies of artists from different backgrounds

and musical

fields. The book associates and interweaves their responses around gender issues in the

musical field:

“Three out of four of the survey’s participants acknowledge that gender has an influence on the

field of

music and sound art. More precisely, 65% of the female respondents, 27% of the male and 62% of

the trans,

intersex, and non binary respondents answered positively to at least ten out of the thirteen

questions with

asked explicitly on the influence of gender on several aspects of the question.”

This survey shows well that gender questions are on your mind almost only if you identify as

female or

if you are from a gender minority.

On a brighter note, more and more queer and feminist collective focusing on technology

and/or music advocating for the visibility of FLINTA* people are

forming. In Belgium I can refer to a couple: Poxcat, a collective based in Brussels

dedicated to support womxn DJs by promoting their work, Psst

Mlle, an intersectional platform promoting underrepresented artists from minorities, Radio

Vacarme, which promotes feminist and queer artists, or Burenhinder, a young art and rave

group mainly based in Antwerp of FLINTA* artists and DJs pushing for the representation of womxn in the hardcore scene.

At the crossover between music and technology, the Vienna-based group Sounds Queer? works on

the intersection of electronic music, sound art and queer activism. They offer a synth

library, workshops and performances. ORAMICS in Poland works on

empowering women, non-binary and queer people on the electronic music scene, as well as

supporting artists from Eastern Europe. DJ Rachael started Femme Electronic in Uganda, a

platform for female DJs and electronic music producers in East Africa. Femme Electronic aims

at addressing the severe gender imbalance in the music industry in East Africa. [MONRHEA]

themselves are very hopeful for the future:

[MONRHEA]: That’s definitely happening. For example, in Santuri, there’s the class that is

specially made to

push

women and non-binary people. And also ANTI-MASS in Uganda who is also involved in the courses.

(…) So the

discussions are definitely going on, and organizations are supporting it and happy for the

future. Because I

feel like if you block someone from expressing who they naturally feel they won’t be happy in a

basic way.

The future is good, I think. At least in Kenya there are organisations for queer people, there

are

organisers who are pushing this.

Moreover, some artists do not feel like there is a disparity of gender inside of their music

sphere

nowadays:

Luisa Mei: I would say from what I’ve seen it’s pretty equal. There’s a lot of non-binary

people, the whole

community has a really good attitude of being totally accepting of every one. I do remember in

school though

I was the only girl in my class. But once I got out and started performing and seeing other

people, and from

what I’ve seen we’re pretty well represented. I mean I’ve performed in New York City which is

probably one

of the more open places and has the greatest diversity so I think I’m lucky to be able to

experience that.

Representation of minorities and the groups fighting for the representation of minorities

find

themselves in more alternative circles.

In more mainstream or academic circles, there is still a lot of work to be done.

During my research, I discovered the Computer Music Journal

published by the

MIT press. You can read in

its description: “For

four decades, it has been the leading publication about computer music, concentrating fully

on digital

sound technology and all musical applications of computers. This makes it an essential

resource for

musicians, composers, scientists, engineers, computer enthusiasts, and anyone exploring the

wonders of

computer-generated sound”. The problem is that 90% of the writers and researchers featured

in this

journal are male. Some of the issues (see for example the volume 45, issue 2 of Summer 2021)

are even

exclusively male.

- “computer”. Oxford English Dictionary (Third ed.). Oxford University Press. March

2008. “1613 'R. B.'

Yong Mans Gleanings 1, I have read the truest computer of Times, and the best Arithmetician

that ever

breathed, and he reduceth thy dayes into a short number.”

- The Applied Mathematics Panel was created at the end of 1942 in order to solve mathematical

problems

related to the military effort in World War II. The panel's headquarters were in Manhattan.

- Megan Garber, “Computing Power Used to Be Measured in ‘Kilo-Girls'”, The Atlantic, October 17,

2013

- Carol Frieze and Quesenberry, “Cracking the Digital Ceiling: Women in Computing around

the World, Cambridge University Press, 2019

- John Fuegi and Jo Francis, “Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 'notes'”, Annals

of

the History of Computing, 2003.

- Jennifer S. Light, “When Computers Were Women”, Technology and Culture, 1999.

- Ibid.

- Lori Cameron, “What to Know About the Scientist Who Invented the Term ‘Software Engineering'”,

IEEE, June

26 2018

- Liz Huang, “Refrigerator Ladies: The First Computer Programmers”, Medium, March 8th, 2018

- Rhizome is an American not-for-profit arts organization that supports and provides a

platform for new

media art since 1996.

- Extract from the article itself

- Abi Bliss, “Invisible Women”, The Wire, April 2013

- El Hunt, “Electronic Ladyland: why it’s vital we celebrate the female pioneers of synth”, NME

(New

Musical Express), 2020

- Tara Rodgers, “Tinkering with Cultural Memory, Gender and the Politics of Synthesizer

Historiography”,

2013

- Julia Eckhardt, “Grounds For Possible Music, On gender, voice, language and identity”, 2018

- Tara Rodgers, “Tinkering with Cultural Memory, Gender and the Politics of Synthesizer

Historiography”,

2013

- Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Of Fiction”, 1996

The lack of narratives from the stance of FLINTA* not only

impacted history,

but also digital

technologies themselves. The algorithms in our devices are created by humans, and thus they

are affected

by our thinking structures. They are designed in specific cultural and economic contexts.

But as they

become natural to us, we stop thinking about where they come from and how they are made:

what narratives

they carry.

As FLINTA* and/or queer people, we are more prone to have to

construct our

own systems for survival

inside the heterocis and patriarchal system we live in. Technologies can offer us a way to

construct

these systems. However, this means that we might have to rethink the tools we use and how

they work. We

like to think about digital technologies as a way to create imaginary narratives as we miss

those from

the past, to invent technologies far from rigid systems, that embrace failures and crashes

as a fuel for

reinvention and disturbance.

Exposing the circuitry

The first thing that drew me towards digital technologies was the relationship between their

interface

and their user. An interface is the boundary layer through which exchanges and interactions

between two

elements take place. Nowadays, the interfaces of our digital tools tend to disappear. When

it comes to

hardware interfaces, they become unified. They come in all shades between grey and black.

They become

silent. Visually and audibly. The time of the heavy chunky computer keyboard that made the

sound of

machinery

when we stroked a key is long gone, as well as the plasticky sound of a MPC2000’s buttons.

They become

less physical. Smartphone’s screens are getting bigger, making us slightly touch the surface

as opposed

to pressing hard several times on a dial button to choose each letter that will compose our

messages.

Everything is designed to be more immediate and efficient. The gestures we operate become

natural,

integrating themselves into our behaviors,

making the user's learning curve ever shorter: “The more intuitive a device becomes, the

more it risks

falling out of media

altogether, becoming as naturalized as air or as common as On one

hand we do not need to take

time anymore to understand how the tools we use actually work. On the other hand, we might

lose sight of

how they work under the surface.

This can come as less of a truth if we talk about synthesizers and electronic music tools in

general,

which still often come with a manual and still very present interfaces, minus the clicky

button sound

from the old days. But do not get me wrong. I’m not against a little help and automation,

otherwise

everything would be pure frustration, and I do not advocate for the return of computers as

heavy as a

rock. What I’m saying is that we don’t think about these tools anymore because they become

natural to

us, like they’re just there. We don’t question ourselves about where they come from, why are

they

working the way they do. We become passive users.

Nevertheless, the tools we use are not innocent. The algorithms in our devices are created

by humans,

and thus they are affected by our thinking. They are designed in specific cultural and

economic contexts and implemented in physical devices. Therefore, algorithms reproduce the

bias of the

conditions under which they are created. We thus need to deconstruct their history and

biases. When we

talk about technologies, we often think about “high tech” technologies.

In her essay

A Rant About

“Technology”, Ursula K.Le Guin

argues that:

“’Technology’ and ‘hi tech’ are not synonymous, and a technology that isn't ’hi’,isn't

necessarily ’low’ in

any meaningful sense.”

The terms “high” and “low” not only judge the performance, but they also place “high

technologies” above

“low technologies” regarding a judgment of value. However, musical tools such as the noise

boxes created

by The terms “high” and “low” not only judge the performance, but they also place “high

technologies”

above “low technologies” regarding a judgment of value. However, musical tools such as the

noise boxes

created by crysoma

for their performances and productions hold the same value as a tool as the latest drum

machine, or

super versatile sampler by

Elektron. I know that the latter is very useful and a noise

box does not hold the same utility as a “Swiss knife” synthesizer. But what I want to

underline here is

the fact that sometimes technologically “simpler” tools are looked down upon or not

considered enough.

“DIY tools”sometimes carry a bad connotation. To re-evaluate

them, Ursula K.Le Guin suggests “to ask

yourself of any man-made object, Do I know how to make one?”.

The purpose

is “to illustrate that most

technologies are, in fact, pretty “hi”. Xaxalxe takes inspiration from more simple

technologies and

instruments that are thus restrictive in terms of what you can produce with it:

“With the tracker of the gameboy you can only play 3 notes at a time. I have 2 of them so I can

play 6 notes

at the same time. I find a lot of inspiration in musical tools that have a lot of restrictions.

That's why

this story of the instrument that has only 5 strings speaks to me a lot. It's a bit like: how

are you going

to convey something emotionally strong with very little material. At one point I was really into

lullabies

because they can be super heavy emotionally, but the melody has to be super simple at the same

time to be

easily remembered and passed down.”

- gadevoi (Xaxalxe) - je nous ai creusé un nid dans mon cœur mais comme tous les oiseaux tu

devais

t'envoler

I think there lies all the poetry about simpler technologies. Making the most out of very

little.

When we think about technologies, the common image we have is something that works.

“Working” means here

that it has a goal and has to accomplish it flawlessly. It is .

This notion of “triumph” makes a lot of sense if we look at the terminology of electronic

music and

technologies in

general: you “launch” a software or “arm” your track. Then you can “trigger” a sample by

pushing a

button on your “controller” and set its “attack”. Maybe your program is going to “crash” and

you’ will

need to “kill” it. This lexical field makes the tools we use for electronic music sound like

a weapon we

are off to combat . Gearing up to accomplish the best

sound ever

heard. But I personnally feel closer to my

tools thinking of them as “cultural carrier bags rather than weapons of In The Carrier Bag

of Fiction, Ursula K.Le Guin uses the theory that the first Technology ever

invented by

humans was a

recipient as opposed to a weapon, shifting the way we look at humanity's foundations from a

narrative of

domination to one of gathering. Besides a more theoretical approach of what our digital

technologies

mean, we must not forget who

actually build those tools. Women have been very important to the music industry as a labor

force. For

example, Fender’s factory used to only hire women, and almost all of them were

Hispanic. It is important

to keep in mind the context of production of our tools: who made them, where they come from.

Constructing our own technological systems allows us to become independent and enables us to

emancipate

ourselves from those major technological narratives. The first interest of Xaxalxe when it

comes to

programming was to “conceive things that can change your everyday life” and “to really have

possession

of [her] own tools, to know everything about them”, meaning where they come from and how

they work. As

we saw earlier, behind most of the tools we use, the chain of production implies the hard

labor of some

in sweatshop production, especially when it comes to our very handy computers that are now

used by

everyone making electronic music.

Nevertheless, it is very hard not to say impossible to free yourself

from such tools. The best we can do here is to keep in mind the commodity chain that

produced the

computer you have on your lap.

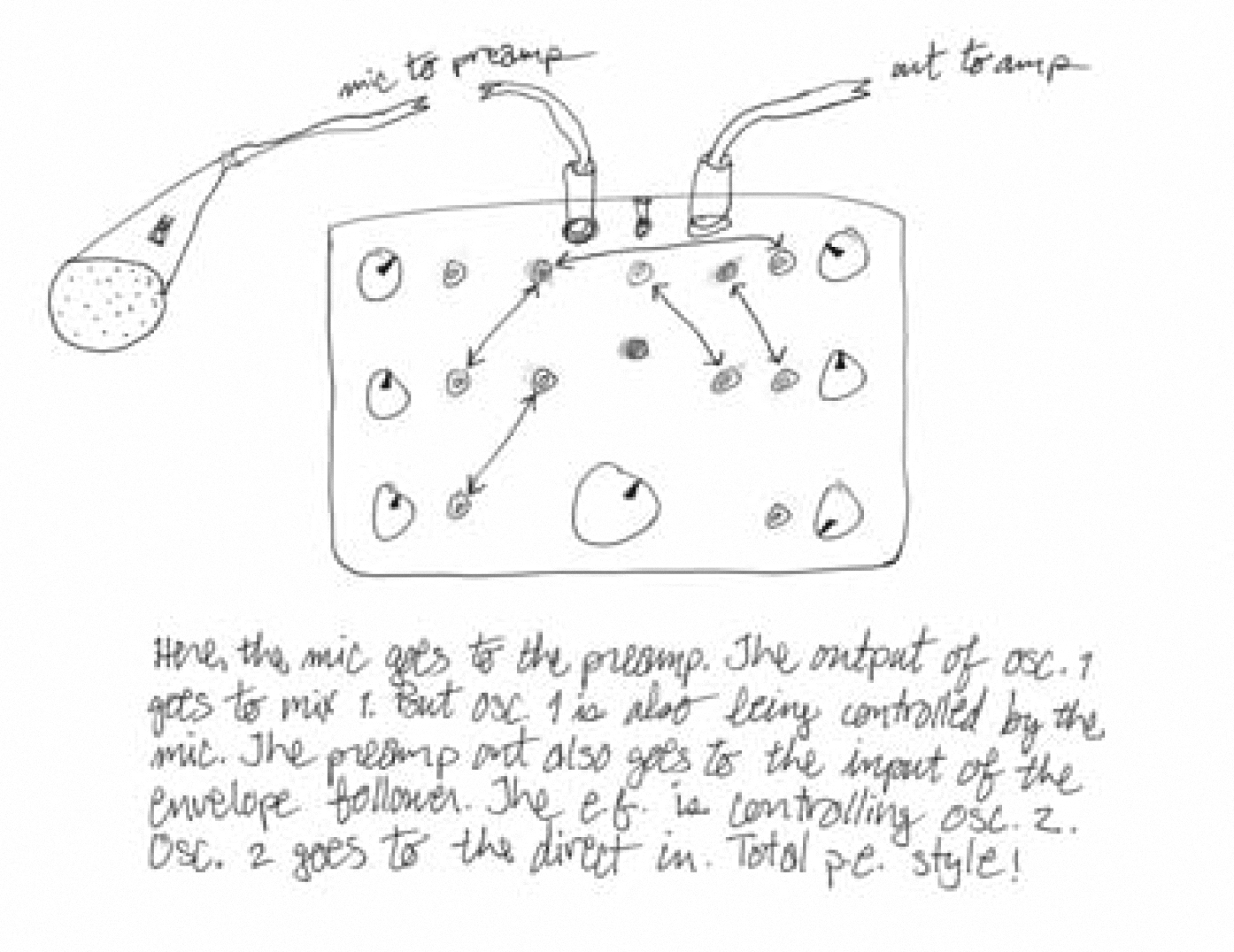

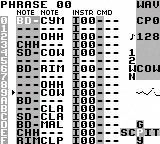

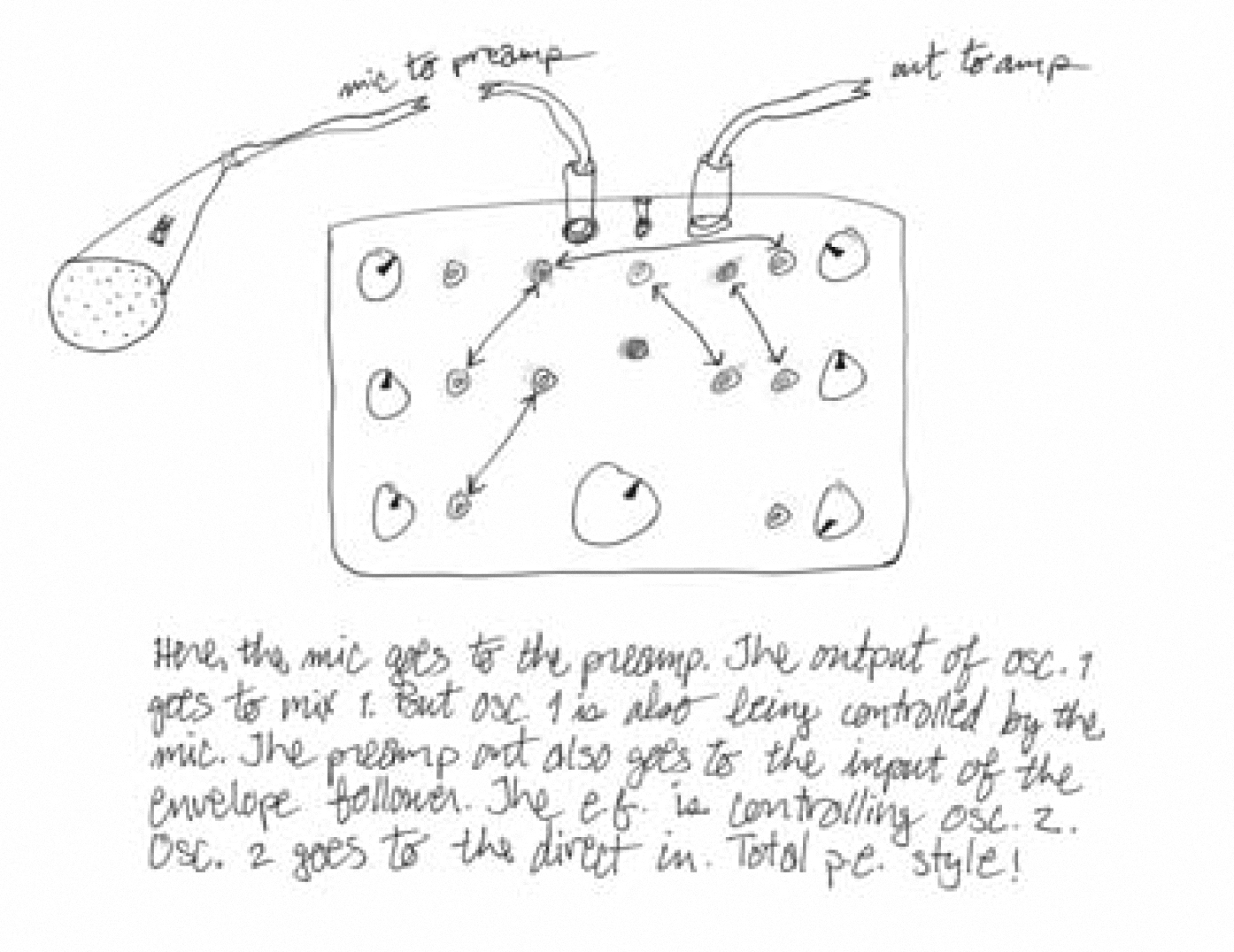

Excerpt from Flower Electronics Little Boy Blue synthesizer manual,

designed by Jessica Rylan, 2006

“Here, the mic goes to the preamp. The

output of osc.1 goes to mix.1. But osc.1 is also being controlled by the

mic. The preamp out also goes to the input of the envelope follower.

The e.f. is controlling osc.2. Osc.2 goes to the direct in. Total p.e.

[power electronics] style!”

When Jessica Rylan talks in Pink

Noise about one of the reasons she built her own synths, she insists on the fact

that “[she] built this thing because [she] did

not want to exploit other people. (…) I’m not going to use an instrument that was made by

slave labor.”

Jessica Rylan used to run her own synthesizer brand: Flower Electronics.

But even if you build your own synth, it remains almost impossible to liberate yourself

completely from

those chains of production. I ran into the problem myself when creating the controller part

of my

synthesizer. First of all, you do not know in what condition the components you purchase

have been

produced. Secondly, I tried to search for ways to produce the PCB in Europe but the cost of

one PCB was

too expensive for me, whereas ordering 5 PCBS in China was less than the price of only one

PCB in

Europe.

- Jessica Rylan - Lonely at Night

Fiona Barnett, Zach Blas, Micha Cárdenas, Jacob Gaboury, Jessica Marie Johnson, and Margaret

Rhee

imagined the Queer Os. Installing the fictional Queer Os would

reconfigure

our technologies by wiping

down all biases at the core of our machines once you situated the cultural position of the

device.

Nowadays, queer artists are applying gender questions to technologies as a means to

reconfigure the way

we handle technologies and the way we view gender and our bodies. They create new

imaginaries as a means

to reboot the system into a more inclusive one:

“The OS will be liable for reconfiguring content generated by hierarchical ontological pasts;

those rooted

in slavery, settler-colonialism, prison and military industrial complexes will be targeted for

special

attention. The OS will be responsible for transposing such content, reordering vertical

relations into

horizontal, circular, reversible, retractable, prescient, and/or prophetic forms, writing code

for

programming that makes explicit and holds space for new forms. (…) Execution of this operating

system is

only possible if one takes into account the context in which a machine is situated.”

Instagram post of Nadja Buttendorf

29th of January 2019

“Only games that are NOT sexist and racist and do not show colonial settlement behaviour

may be played!”

transCoder, a queer programming anti-language.

2008-2012

Queer Technologies critiques the heteronormative, capitalist, militarized underpinnings of technological architectures, design, and functionality.

System recovery, re-programming our technologies

One of my favorite anecdotes in the history of technologies and electronics is the “problem”

encountered

by Americans and Soviets during the planning of the Apollo-Soyuz mission, launched in 1975.

The purpose

of the mission was to connect two spaceships, one from each country. Existing docking

systems, as Soviet

and American engineers had conceived them, involved one spaceship: the “male”, and the

other: the

“female”. Neither of both sides wanted to be the female spaceship, as it would be

“penetrated” by the

other. In the end, the only solution was to design a universal docking mechanism: The

Androgynous

Peripheral Attach System. This system “could assume the active or passive role as It took two

more years to conceive the new docking system. Needless to say that there is a lot to

deconstruct here,

as for example the alienating view of the sexual act as a non-reciprocal and unequal act,

only involving

one male and one female counterpart. Thus, it erases a lot of living experiences and

identities, by

presuming hetero-cis-normativity. Departing from this, we can start to rethink the

technologies we use,

and even rethink the concept of gender and our bodies as human beings. Noam Youngrak Son, a

non-binary

designer, wrote The Gendered Cable Manifesto, published in 2020:

“By applying this metaphor of gender applied to the cables back to human, I speculate a

fictional society

where people’s gender is functioning like that of cables. In this sci-fi, society consists of

gender-neutral

post-human bodies with more than two-gendered (though it exists in a broader, non-binary

spectrum) genitals

each. Their sexual intercourse happens on a big-group scale involving countless connections of

genitals. Due

to multidirectional connections that they make, the intercourse is not limited on the ground

surface but

forms an architectural construction made of human bodies. (…) Anyone who doesn’t fit neatly in

that category

might be comparable to the gender-non-conforming ways of connection, such as twisting the wires

together.

Those queer ways of cable connection are not usually recommended since it is not secure enough

and may

arouse confusion.”

Musical technological tools as well as the digital space and other technological devices can

be a means

to re-invent and imagine your identity in a way that you could not achieve otherwise.

Nowadays, we see

some influential queer figures of the electronic scene using technology as a new way of

expressing their

gender. Amongst those I can name Arca (she/it), a Venezuelan and

non-binary

musician whose work is defined by themes of renewal, expansion and transformation. Arca is

always

reinventing its body through exoskeletons and 3D modeling, inscribing its work in the same

vein as

Laboria Cuboniks who wrote the Xenofeminism manifesto published

by in 2015,

advocating for the use of

technologies “to re-engineer the world” and for “gender hacking”: “Xenofeminism indexes the

desire to

construct an alien future (…) If nature is unjust, change SOPHIE

(she/her) heavily used references to technology with very synthetic and plasticky sounds in

her music

production. She did not advocate for anything “fake”, but on the contrary, she advocated for

a world

where people from gender minorities could exist freely, a world free from gender oppression.

SOPHIE’s

distorted and superhuman voice in Immaterial sings an anthem celebrating gender-fluid

joy. Her sudden

passing in early 2021 was felt like a great loss by a lot of people of the electronic music

scene (fans,

DJ, producers…), but most of all for those from the LGBTQIA+ community.

- Arca - Non Binary

- SOPHIE - Immaterial

In Eilein’s experience, technology can be very emancipatory.

It can enable you to play with your gender identity through techniques like pitch shifting,

resulting in

more confidence:

Im-ma-ma-material, immaterial

Immaterial boys, immaterial girls

Im-ma-ma-material, immaterial

We're just, im-ma-ma-material

(I could be anything I want)

Immaterial, immaterial boys

(anyhow, anywhere)

Immaterial girls

(any place, anyone that I want)

Im-ma-ma-material, immaterial

SOPHIE, ”Immaterial”

2018

Eilien: (…) [F]or now I haven’t been using that much live

manipulation of my

singing but more samples of my

singing. But I think in regard to this gender related stuff, in my older pieces and sounds there

has been

this urge to somehow hide my voice with pitch shifting and some effects. Or maybe not to hide it

but to

multiply it, so it would be less like “oh there is this one gendered voice”. I’ve found it

really nice and

emancipating. But I feel that during the recent months I’ve gained security in my voice. I

started to make

sounds that have barely no effects at all, where the voice has been unprocessed. But definitely

I think

pitch shifting, multiplying is funny and emancipatory to be able to play with your gendered

voice, make it

less gendered or confusing.

Celebrating crash as a reboot strategy

If queer artists now reclaim technologies as a means to create new imaginaries,

technological tools have

always been important for the FLINTA* community and minorities in

general.

Legacy Russell recounts her

experiences with the online space in Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto:

“LuvPunk12 as a chatroom handle was a nascent performance, an exploration of a future self. I

was a young

body: Black, female-identifying, femme, queer. There was no pressing pause, no reprieve; the

world around me

never let me forget these identifiers. Yet online I could be whatever I wanted.”

Now, the online space can help bring minorities together by creating communities, but

cyberspace was even

more essential

back in the late 20th century as the circulation of information regarding queer experiences

was very

limited. It permitted

people to reinvent their gender or racial identity. Moreover, there was more than one online

space

before, being now the Internet.

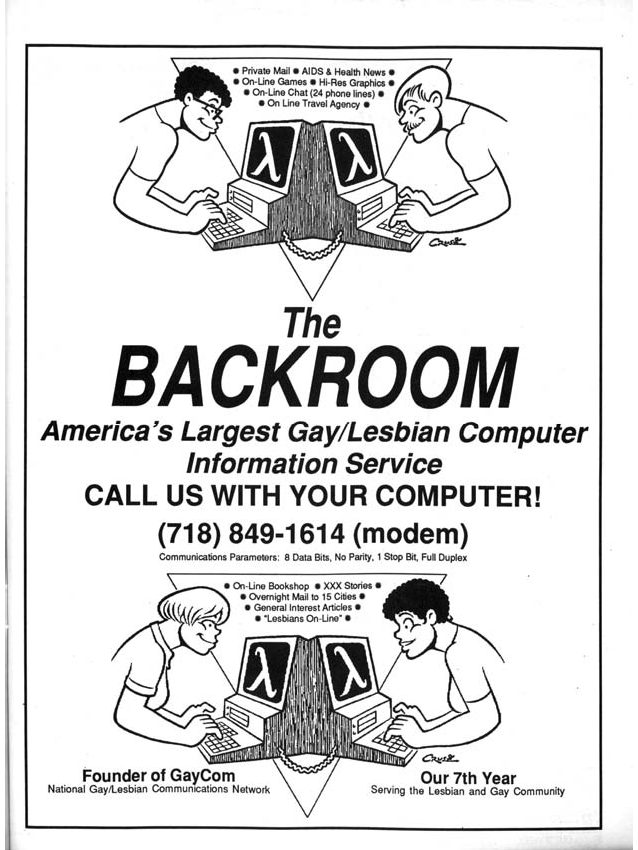

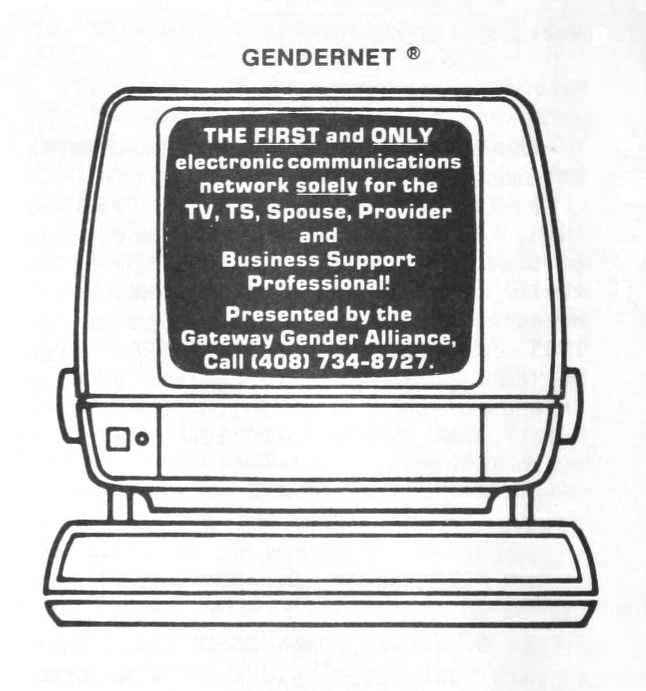

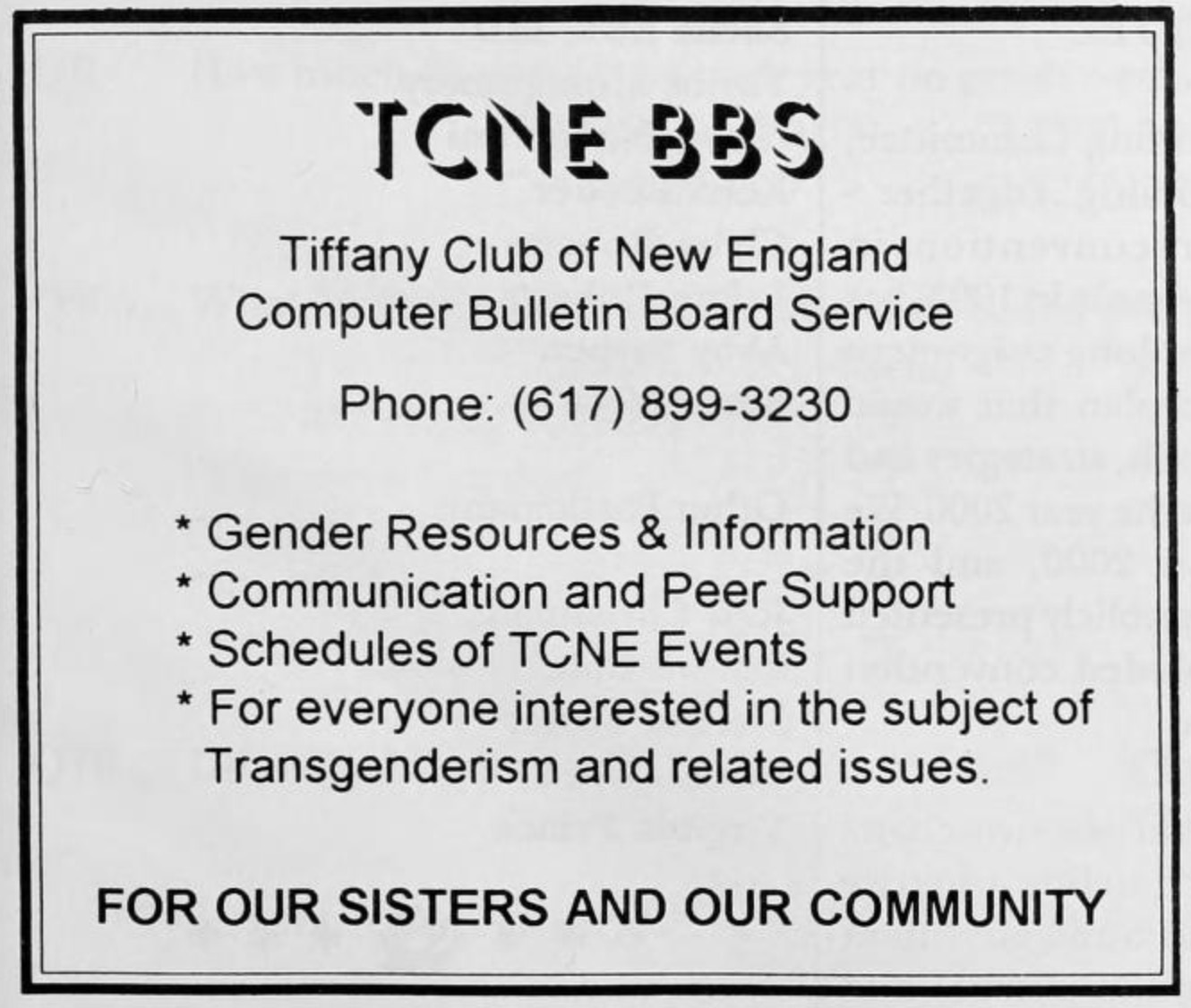

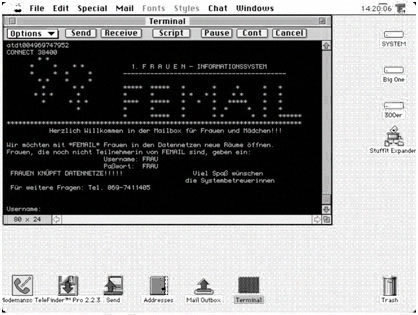

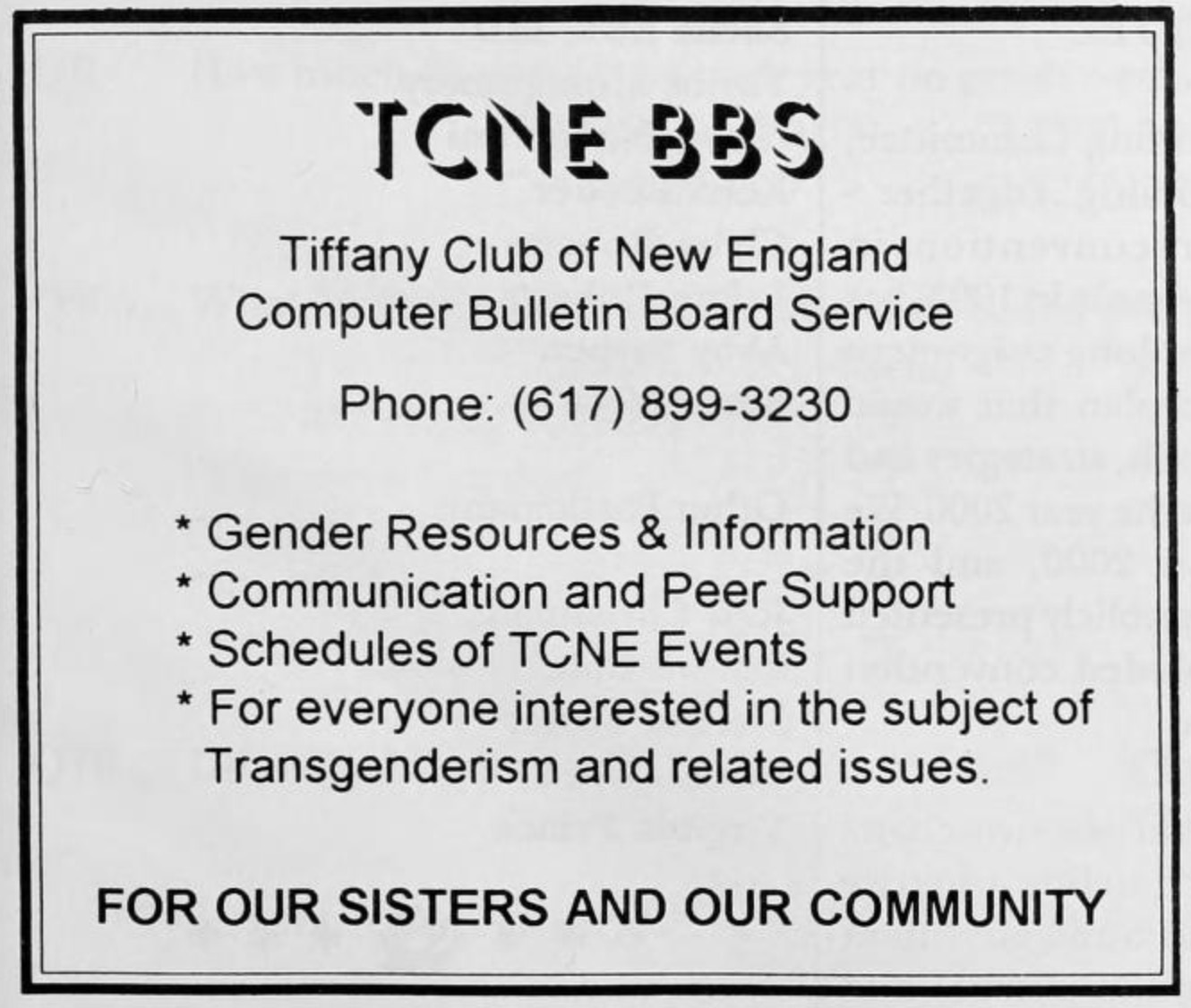

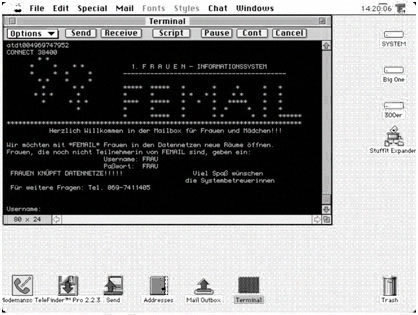

BBS were very important to the queer community. BBS stands for Bulletin Board System, also

called

Computer

Bulletin Board Service, CBBS. Bulletin Board Systems can be considered as a precursor to the

modern form

of social networks and the Internet. They were mostly used between the 1980s and the mid

1990s. BBS

allowed users to dial a number through their modem and access an online text-only space

where users

could post messages. “In the 90s, almost every major trans magazine had explainer articles

on how to use

the BBS” says Avery Dame-Griff, founder of the Queer Digital

History

Project documenting pre-2010 LGBTQ

digital spaces online. These BBS sometimes presented themselves with a fake front-page for

which you

needed a key if you wanted to enter the BBS:

“Users trying to access Feminet would dial in and be directed to a completely different site.

There they

would be asked for a password, which was listed in the back of ‘TV-TS Tapestry’, one of the

major

transgender zines of the time. If they did not have it, they’d be bounced.”

This shows how digital tools can be an important tool of emancipation for minorities in

general, allowing

them to create a sense of community and to form alternative spaces. As a matter of fact, the

vast

majority

of the people I know who take an interest in reflecting on technology on a theoretical level

or who are

very

into open source are usually female-gendered, from gender minorities and/or queer.

As a queer person and/or member of the FLINTA*+ community, we

often have to

build our own survival

system inside of the hetero-cis and patriarchal system we live in. For a large amount of

people still,

if you happen to not be what they expected of you (meaning hetero-cis or a very well behaved

cis

gendered female), you are considered as odd, dysfunctional or even as a “failure”.

The Backroom BBS

Area: New York, NY

Years of activity: 1986-1997

Puss N Boots BBS

Area: Richardson, TX Grand Prarie, TX

Years of activity:1991-1995

GenderNet

Area: Sunnyvale, CA; later Oakland, CA

Years of activity: 1984 - ?

TCNE BSS

Area: Waltham, MA

Years of activity: 1992-1997

FEMAIL BBS

Area: Frankfurt, Germany

Years of activity: 1993 - ?

We soon realize that “we will never be given the keys to a utopia architected by and thus have to conceive our own systems to live in,

where this

“failure” is viewed as a potential.

Considering Muñoz:

“Queerness is not here yet. Queerness is an identity. Put another way, we are not yet queer. We

may never

touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with

potentiality. We have

never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an identity that can be distilled from the past

and used to

imagine a future. The future is queerness's

When Muñoz wrote that “queerness is an identity” he qualifies it by its potentiality that can

be “used

to imagine a future”. Something that you can never pin down, that is ever evolving and thus

that is a

fuel “to imagine a future”. In their interview, [MONRHEA] states that "personally [they] go

by

he/she/they and I use “they” because I feel like there is so much duality. Why should we

pick one

instead of picking freedom?”

This concept of something open and forever fluid is as present in my practice about music and

technology

as

in my practice and research about inclusive typography with the collective BYE BYE BINARY.

Camille

Caroline Circlude Dath,

a member of the group, wrote a manifesto for us that we give to each institution we visit to

make an

intervention (the original text is written in French,

I did my best to translate it as precisely as possible):

“To invite Bye Bye Binary within an institution is to bet on research and experimentations. It

is to work

with partial shapes, forever evolving and in construction, opening up collective imaginations.

(…) Bye Bye

Binary is not a coat of queer varnish on the shit that surrounds us. Bye Bye Binary is not at

your service.

Bye Bye Binary is not only functional. Bye Bye Binary is L O V E & R A G E.”

C°C

In Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, Legacy Russell refers to the notion

of Glitch

as a source of power for minority

groups. The glitch in the technological field is a sudden, usually temporary malfunction or

fault of an

equipment. Legacy Russell thus sees the glitch as an of “nonperformance” and “refusal”. She

uses this

term from the mechanic world to see how we can use it in our

world.

The image of the glitch also

renders the error in the system visible. A glitch is usually nothing you can see or hear:

“We are seen and unseen, visible and invisible. At once error and correction to the 'machinic

enslavement’

of the straight mind (...) We cannot wait around to be remembered, to be humanized, to be seen.”

I think there is so much potential not only in deconstructing the technologies themselves but

also in

rethinking our identities and bodies through technologies. I like to reflect on the relationship

we have

with our electronic instruments in terms of exchange between us and the machine. How could we

design a

machine that we do not have total control upon, and thus that is not only a one-way “request and

response” interaction but an “interaction with an interface [that] might transform both the user

and the

- Zach Blas, Micha Cárdenas, Jacob Gaboury, Jessica Marie

Johnson, and Margaret Rhee, QueerOS: A User’s Manual, Fiona Barnett, 2016

- Alexander Galloway, The Interface Effect, Cambridge: Polity, 2012.

- Ursula K.Le Guin, A Rant About “Technology”, 2004

- Ursula K.Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, 1996

- Tara Rodgers, Pink Noises

- The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula K.Le Guin 1996

- Abigail Ybarra: The Queen of Tone, She Shreds, Issue 11, 2016

- David S. F. Portree, Mir Hardware Heritage, March 1995

- Laboria Cuboniks, Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation, 2015

- Transgender women found and created community in the 1980s internet, Emma MacGowan, 16th of

June 2022

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, 2009

- Away From Keyboard. It is different as IRL (In Real Life) which suggests that the life we

experience

online is not real.

Melting interfaces

The interface -or panel- was one the main points of focus while I was conceiving my

synthesizer. I tried

to encourage the attitude of “letting go” with the design of the panel. I did not want the

layout to be

too readable, with everything aligned in straight lines like the usual layout you find on

most

synthesizers. Therefore, I tried to find another system which is far from random but looks

like it when

you first

approach the machine. Nothing is written on the panel in terms of words like: “oscillator

1”, “attack”,

“decay”, “crossfader”… But you can see an engraved pattern making it clear that there are

two parts,

each being one oscillator with their own envelope, granular synthesis etc. The mini-jack

in-between the

two

“systems” is the crossfader with which you can decide to hear

both oscillators at the same time, to make one louder than the other, or to completely mute

one. I was

interested in creating an interface that was less readable so that I could abandon some

habits and

mechanisms that you may have while producing.

You can connect the synth with a wide variety of sensors. The more obvious thing would be to

use a

potentiometer, but what might interest me the most is to plug sensors that can read

parameters of the

environment you are playing in. Data from the environment will influence some parameters of

the sound on

which we do not have control anymore.

- 1 - Plugging nothing but potentiometers and having total control on the parameters of sound.

- 2 - Plugging some potentiometers and some sensors getting data from the environment. This

would result

in more of a collaboration between the machine, its user and the environment.

- 3 - Plugging in nothing but sensors and getting data from the environment. Therefore having

no control

at all on the sound. This method removes the user from the scheme. I think it results in a

very poetic

thing, letting the synth and the environment work together while the user is only an

observer from the

outside.

The construction of this synth also carries an ecological value. Because of its really basic

electronic

wiring you can easily replace parts instead of just tossing away the machine. I like to

think of it as a

potential evolution of the machine and to not think of it as a finished product. I tried to

think about

the future of this synthesizer in its conception itself. Because it is an open-source

project, you can

adapt it to your needs and liking. Therefore, the machine can be adapted to another

environment. All the

files for the construction of it are available. You can thus open the files and tweak them

to change the

sounds that the synthesizer makes, the layout of the panel etc.

A message is written on the PCB to engrave the values it carry to

its very

core::

“Being queer means inventing your own systems, bending circuits.

Queerness is having to hack and reconfigure.

Queer technology stands against efficiency and performativity.

Queer systems are fluid, resisting rigid structures.”

Luisa Mei explains that creating her own structure when it comes

to

interfaces in SuperCollider makes her

producing tools feel closer to her and her practice:

Luisa Mei: I think it’s probably not the type of sound that feels closer to me but maybe the

structure of

the interface that I use. In Ableton there are so many presets and things that you can use and

you can map

it very easily to your controller, it’s just very convenient. But the thing I enjoy about

SuperCollider is

that I can build my own sort of interface, and how I want it to be.

Other artists mentioned that using alternative tools such as music coding where you have to

build

everything from scratch gives them more freedom of creation, because nothing presents itself

directly

into a pre-made interface that may guide you in your creation process:

[MONRHEA]: It’s a tool, an opportunity not to be on a grid system

that has one

purpose: it has to be this

way. You’re using a tool that is made from freedom, you just go however you feel.

- Luisa Mei - I am The Metal Son

- [MONRHEA] - or maybe

The lack of interface when doing pure code implies that you do not necessarily know in

advance what you

are going to land on musically wise. In some cases, it might also help to go beyond typical

thought-process for producing:

Xaxalxe: There was a kind of challenge which was to do musical stuff with as few lines of code

as possible.

For example you can put all the numbers from 1 to 10 in loops, and you can try to modify that

afterwards

depending how it sounds. Since you're not saying to yourself “oh I'm going to do a sinusoidal

wave, I'm

going to do a filter, etc.” It's hard to imagine what the code you write is going to sound like.

Because my system is DIY, it is sometimes prone to noisy errors,

like sudden change of the sound then

getting back to normal or sudden outbursts of percussive sounds in the middle of a drone

session. The

goal is to embrace the bugs and defaults. Embracing the silence it sometimes makes when it

crashes as a

Design of the synthesizer panel

temporality that the machine creates as an integral part of the performance. I play in response

to the

machine. I wait for it to restart so we can begin another chapter of the performance. As I do

not know

when it might or if it will stop, I have to be flexible and not come into the performance with a

plan in

mind. As opposed to having a structured composition, I have to feel what evolution of the sound

could go

next in the heat of the moment. You have to pay extra attention to the sound.

Eilien: In SuperCollider you don’t see the waveforms. Well you can but it’s maybe not what you

think about

when you first start with SuperCollider so I could focus on listening.

The interfaces we play with are not just important to us as producers, but also as live

performers. Using

alternative tools can help to rethink the whole act of performance. We are very much used to

the one-way

dynamic between the performer on stage and in front of the public in a sort of powering

position, and

the public staring in one direction towards the performer. In terms of the setup nowadays in

electronic

music, we are very used to seeing a live performer only coming on stage with their laptop

and a

controller. Moreover, the controller is sometimes hidden behind the laptop. This makes the

whole act of

performance less visual as it is as if the mechanism behind the music was hidden from us. It

is not that

there is anything wrong with it, if it is how you feel comfortable performing. I have seen

many live

music with this precise set up that I really enjoyed.

Nonetheless, I find it interesting to think about these kinds of positions in space and also

the very act

of performing. Sometimes using different types of gear can lead to re-configure

relationships between

the performer, their tools and the audience:

[MONRHEA]: When I came to SonicPi, it taught me to tap into a more performative aspect. There is

a very

interesting feature in Sonic Pi where you can set “transparency” and set background visuals so

you can use

that to tell a story or just be creative in various ways. (…) You can customize it depending on

the

performance. Depending on how you’re feeling or what message you want to share. Compared to

Ableton, if

we’re talking about the user interface, it’s much more structured and in tones of grey. With

Sonic Pi, you

can even use the interface to tell a story with your music with the transparency feature I

talked about

earlier.

What [MONRHEA] mentions here is frequently seen in Algoraves. Algoraves (from an algorithm

and rave) are

events where people listen to music generated from algorithms. The performances feature live

coding,

meaning that we can see the performer writing the code producing the music in real time. We

can thus

connect a change of the code that we see with a change in the music that we hear, despite

understanding

what the code really means. TOPLAP, a collective born in 2004

wrote The TOPLAP

manifesto in which we

can read:

“We demand: Give us access to the performer's mind, to the whole human instrument. Obscurantism

is

dangerous.

Show us your screens. (…) Code should be seen as well as heard, underlying algorithms viewed as

well as

their visual outcome.”

It can be thought of as one way to share what is happening inside the computer of the

performer.

Moreover, [MONRHEA] mentions that with Sonic Pi, “you can even use the interface to tell a

story with

your music”. Because Sonic Pi allows you to produce sound and visuals at the same time, you

have the

capacity to add a narrative layer to the music, also controlled by the performer and not

visuals

produced by someone else.

Luisa Mei: I think for everyone to make tools is another level to really figure things out about

yourself

because since you’re building it yourself you can decide how you want to interact with it, and

you have to

figure out how you want to feel when you’re performing.

Thus, although it does not necessarily have something to do with using alternative tools, I

thought

worth

mentioning that some of the interviewee expressed a will of taking care of their audience:

crysoma: When we play live, we always worry about how loud it's going to be. We never crank up

the

volume to its maximum, overpowering the listener. We try to be in a form of listening care. We

saw lots of

noise concerts in Besançon, and we saw a lot of male artists who did not care about blowing up

everyone's

ears.

More and more queer and feminist groups working towards giving more visibility to FLINTA* artists are

also actively thinking about making the dancefloor a safer space, not only in terms of

anti-harassment

policies but also by of taking care of sensory issues and the integrity of the listener’s

body.

Workshops are being created to work on these issues, like Psst Mlle’s Deconstructing the Dancefloor I -

Rethink workshop in Brussels, where the public attending the live performances

could

contribute to the

creation of what they would consider the ideal space to attend these lives.

Weird (Queer?) sounds

“Have you established any relationship(s) between noise music and feminism/queerness? If so,

what would they

be?”

Maëva from crysoma: To me there is this alternative culture

situating

itself in the DIY movement, of emancipating

yourself from a melody, from the rules, from a structure. Finding ways to deviate from expected

things. It's

also more of an un-normative practice. I also find it important within my practice to find tools

that give

you infinite ways of producing. There is also this idea of being weird I think (laughs).

- crysomatening: crysoma - Azamide Aplenfen

This notion of “weirdness” comes up often when I discuss music production with my FLINTA* peers. We will

see that this notion of “weird“ comes under different forms like: “different”, “discarded

objects”,

“sounds that don’t resemble others” etc. Many of them express that using or creating

alternative tools

allows them to “deviate from expected things”. Like Maëva stated above, it allows them to

create sounds

that seem more close to them.

Back when I started the construction of this synth in November 2020, I was learning at the

same time how

to produce electronic music. It is not that there is truly a “how”. It was more about

learning the

lexical field of electronic music (ADSR envelope, triggers, sequencers…) and how sound works

in the

physical sense, learning about the different kinds of synthesis and so on. I was juggling

with learning

PureData, basic electronics with Arduino, and how to produce a sound overall. I thus had no

idea of what

would come out of my experiment as I was patching something with something else, then

hearing what it

produced. I really enjoyed this kind of ignorant way of creating. This practice could be

considered far

from “rigorous”, and thus far from “a form of training and learning that confirms what is

already known

according to approved methods of I feel like

sometimes not

knowing what you are doing can be less restrictive in some ways and create beautiful and new

things you

would have never found otherwise.

Nevertheless, now that I have gained some knowledge, I try to combine both approaches of

mastering a

practice without losing the will of using material you are not supposed to use the way they

were

conceived to, or turning the knobs in every direction possible without knowing what you are

going to

land on.

- Laura Conant - Sound Test of the Synthesizer

I also like what granular synthesis represents in itself. You can chop a

pre-existing sound or a live instrument and rearrange it, making it sound totally different.

You can

also choose to lay this newly recomposed sound on top of the original piece or not. It

really resonates

with me if you let this aspect of granular synthesis resonate with the notion of “remix” in

Legacy

Russell’s work:

“Queer people, people of color, and female-identifying people have an enduring and

historical

relationship to the notion of ‘remix’. To remix is to rearrange, to add to, an original

recording. The

spirit of remixing is about finding ways to innovate with what’s been given, creating something

new from

something already there.” Glitch Feminism, Legacy Russell, 2020”

That might also be why I enjoy performing DJ sets that much. Creating a story with

pre-existing materials

that might resonate totally differently depending on which track you lay on it, or just the

track before

and after. A 140bpm track with ethereal beats can be the energetic moment in an ambient set,

or be a

moment of relief and trance like introspection in a high energy set. Once again it’s all

about the

context. Authentically Plastic, a member of the Kampala-based

queer

collective ANTI-MASS says: “I like

to treat genres in the same way I look at gender (…) Corrupting and connecting disparate

things is

They interweave and draw connections through

industrial

techno, noise and qgom. Creating a

is essential and a crucial political act in an

environment

where the repression and

stigmatization of LGBTQIA+ people is still very much going on in state where having a

relation with a

person of the same sex is still a crime.

- Turkana & Authentically Plastic - Diesel Femme

Getting back to the synthesizer, when it comes to the sounds it produces, they land between

noise, drones

and percussive rhythms.

I always really enjoyed noise and drones, as a listening experience but also because of the

meaning

these practices carry if we read

them through a queer and feminist lens.

Noise is considered as something undesirable that we try to mute, as overall we try to mute

female-gendered people and those from gender minorities. For most, a virtuous woman is

considered quiet

with elegant manners. Someone talked to me about the first concert she saw of . She was performing the opening act for a Björk concert

at the time,

years ago. While she absolutely loved the

performance of Peaches, a lot of people in public were quite disconcerted and shocked in

front of this

fabulously energetic and loud woman, who really did not care about swearing. We can also see

in history

and myths the bad women are often noisy like the sirens of the sea, or witches and their

machiavellian

laugh. But “[t]he purported noisiness of femininity is intensified by certain

co-constitutions of race,

class and

The practice of noise music can be a way of deconstructing a unique perspective, the noise

being an

arrangement of micro-events within a whole, in which it is necessary to immerse yourself

completely:

“noise as a site of disturbance and productive potential” (Tara Rodgers). In physics, it is

considered

as unorganized sound: “The distinction between music and noise is a mathematical form. Music

is an

ordered sound. Noise is a disordered sound.”. I enjoy the bodily nature of noise, it is more

palpable.

It is all about affects, as you cannot picture the sound in your head because we live in the

realm of

pitch and we enter the world of textures and impacts. Whereas if I hear something like a

melody, I can

picture which note is above which one. The experience of feminine and queer bodies also

situates itself

in affects. In Live Through This: Sonic Affect, Queerness,and the Trembling Body (2015), the

researcher

Airek Beauchamp states that noise and making noise “helps break down the essential binary

between

encoded language and un-encoded sound.”. In his research, he

worked on ACT

UP!, “the noisiest and most

politically effective of the AIDS advocacy groups from 1987 through 1995”.

He analyzed the ways in which

ACT UP! used both noise and silence in their protests, as a means to work on the idea of a

queer

communication, of a queer sound:

“Rather than syntactical sound, noise communicates in trembles, resonating in both

the psyche

and in the actual body. Noise worked to unify disparate parts of identity–and disparate

identities–a

coalescing rather than normalizing process, a trembling vital to queer

Authentically Plastic states that “when it’s radical, music can allow a marginalized body to

exist, to

express itself, in a kind of symbiotic Sound

can carry a

lot of meaning for each and

every one of us. Our different encounters, our culture and overall our experiences shape the

kind of

music we might create or listen to: “[m]usic, therefore, is not only intimately interwoven

with our

personal identity, it is also an excellent medium for accessing life narratives.”. That is

exactly what

Sarah Hennies tells us about her own instruments in her essay Queer

Percussion:

“I didn’t know why I wanted the bells. I just kept buying them because they were cheap, and I

liked the

sound, and I’ve always liked the idea of making art with trash. But why was I drawn to making

music with

discarded objects? By the time I began collecting bells, I was already aware of the tendency for

my music

to reveal something about me before I consciously realized it myself. (…) Now I can only think

of the bells

in all their worthlessness and complexity as a very thinly veiled sappy metaphor for discarded

queer life,

and for the past few years that has felt like the right thing to do.”

Consciously or not, our tools for music production can say a lot about us and even the music

we produce

or listen to as well. In her essay, Sarah recounts the moment she realized she was

transgender was

“during a concert by a British band called The Spook School at the NYC Popfest” when she

heard their

singer say “What’s next? Oh yeah, another song about being transgender!” While fifteen years

earlier,

she was obsessed with their song For Today I Am a Boy where the singer says:

“One day I’ll grow up

and be a beautiful woman

One day I’ll grow up

and be a beautiful girl

But for today I am a child

For today I am a boy”

One day I'll grow up,

I'll be a beautiful woman.

One day I'll grow up,

I'll be a beautiful girl.

One day I'll grow up,

I'll be a beautiful woman.

One day I'll grow up,

I'll be a beautiful girl.

But for today I am a child,

for today I am a boy.

For today I am a child,

for today I am a boy.

For today I am a child,

for today I am a boy.

One day I'll grow up,

I'll feel the power in me.

One day I'll grow up,

of this I'm sure.

One day I'll grow up,

And know a womb within me.

One day I'll grow up,

feel it full and pure.

Antony And The Johnsons, “Today I Am A Boy”

2005

If music can say a lot about us, and even make us realize things about ourselves, then it

becomes

important for some FLINTA* artists to create sounds that feel

close to them:

Eilien: Maybe I haven’t been thinking about it this directly. But I think maybe I

have had

the feeling that

it’s hard to use some pre-existing sound libraries or presets sounds or anything because the

majority of

sounds that you find are always referring to some genres, movies, a specific time… And many of

these

associations, somehow, I don’t want them (laughs). (…) If you would really interpret these

tendencies, I

think it could be thought of that way that like these sounds refer to culture and a cultural

history which I

don’t think resembles me that well because many of those sounds are so related to a pretty male

dominated

culture.

I myself take a great deal of effort into creating my own sound via sound design, starting

from scratch,

so that the sounds I use feel close to me and do not resemble other sounds. I love to use

plugins or

hardware with weird approaches to synthesis, sampling, effects etc. Do not get me wrong, it

is not to be

snobbish or because I do not want to use “the synth or sampler that everyone uses”. I own an

Octatrack

which is far from being an alternative tool, and one of the most famous samplers in

electronic music

(still I would argue that because of its immense complexity, possibilities are unlimited and

you can

really shape it close to your practice). But it is just easier to produce peculiar sounds

with peculiar

tools as Eilien declares:

Eilien: About these sounds that don’t resemble others, it is easier to make them

with tools

which are not so commonly used. To look at sound or music from a really weird angle.

Using “tools that are not so commonly used” can also make it easier to not be compared with

other

artists:

Xaxalxe: It's clear that I never felt compared with other people who are making

music

because I'm just doing my thing. There are maybe 2/3 artists who are doing similar stuff but

it's like a

project that existed for 3 years in 2014 or something. It allows me to make music without

comparing myself,

which is pretty cool and liberating. (…) I think I like this thing about getting out of

comparisons,

otherwise you're going to be like “the girl who plays the guitar” you see. Whereas if you have a

practice

which is less readable it can allow you to get out of that.

Xaxalxe also recalls that producing is rarely just about using one tool, but that all the

different gears

that you use for producing music is also creating your own system:

Xaxalxe: When you assemble different machines, it's a bit like creating your own

systems as

well. For example, nobody uses the same system as me. For example I watch videos of effects

pedals and it's

always people testing them with a guitar, and I always wonder “But what would it be like with a

Gameboy?”.

To the question: “Do you think that alternative ways of creating music can be emancipatory

for women and

gender minorities artists?” [MONRHEA] replies:

[MONRHEA]: I will definitely encourage female artist and queer people in general

to use

SonicPi or other music coding software cause Ableton and FLStudio are already quite male

dominated. If we

embrace such a tool that is still growing in his community. You can customize it depending on

the music

performance. Depending on how you’re feeling or what message you want to share. (…) It’s a world

of

different possibilities. So we have a chance and an opportunity to take that space in that

world. There is a

space for us I think.

The economy of open source project

and alternatives technologies

Several of the interviewees mentioned the economic aspect of making your own tools, or using

alternative

ones:

Maëva from crysoma:: I do not have any bases in Ableton so it's always Solène who takes care of

that.

Even to record and

everything. Finding a way to be autonomous without software or without an instrument that you

don't know how

to use is super important and it feels super nice. It's a way to free yourself from all the

rules and make

sound without necessarily having any prior knowledge. You always have to pay for software and

instruments

are super expensive. So even economically, making your own tools is interesting.

The vast majority of music-producing software is really expensive. You can try to crack it,

but you may

not have every plugin that comes with it, or you expose yourself to a potential crash of the

software

during the production or worse, while doing a live performance. Creating your own tools can

spare you

this hassle, even if not using any renowned software can be hard as Xaxalxe mentions:

Xaxalxe: When I started making music with computers, it was with open source software. That's

also why I

had a lot of driver’s issues and stuff. I was using Ardour, an open source DAW. It was either

that or LLMS

but Ardour is more developed. It's super advanced but like all open-source software, you have

some random

bugs and when you make music and you lose what you've been doing for an hour it's a bit

annoying. I had done

concerts in 2016 when I started to organize parties. Back then my set up was very precarious. I

hadn't found

an open source autotune that I liked, so I used a plugin meant for Windows that I emulated with

Wine. I

reconnected it with a specific Linux distribution where they develop their own software. In this

distribution there was a software that allows you to patch other software together, to re-record

the

patches, but it was really a hassle. Recently I installed Windows on a 10-year-old computer

because I just

wanted it to work, so now I have Ableton and that's it.

Eilien: (…) All of those coding, DIY methods for producing sounds are

very technical so because of that it

might be hard for emancipation. Though I feel it has the potential. But in other ways it’s super

accessible

because for example SuperCollider doesn’t cost anything.

A problem raised by Eilien is that “DIY methods for producing

sounds are very technical”, thus demanding

a lot of time and sometimes a steep learning curve. I want to mention that it is a

privileged situation

to be able to learn new things on top of having to produce music, or working another job. If

I was

personally able to learn all of this in two years in addition to all my other obligations is

because I

did not have to work during my studies and I do not want to leave this crucial component

behind. It can

thus make DIY methods for producing hard as a tool for

emancipation.

- Forking is to create a new branch out of a primary direction or based on a primary distribution in digital technologies.

I use it in this context to indicate that FLINTA* artists branch out of the main narrative which is male dominated.

- Jack Halberstam, “The Queer Art Of Failure”, 2011

- Legacy Russell, “Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto”, 2020

- Lloyd Gedye, “ANTI-MASS’ queerness is in both genre and gender”, New Frame, 2021

- Angel E. Fraden, Interview of Authentically Plastic, Okay Africa.

- Peaches, is a Canadian electroclash/punk rock musician and producer.

- Marie Thompson, “Feminised noise and the ‘dotted line’ of sonic experimentalism”,

Contemporary Music Review Vol.35, 2016

- Airek Beauchamp, “Live Through This: Sonic Affect, Queerness,and the Trembling Body”, 2015

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Marion Wasserbauer, “On Queer Musical Memories”, “Grounds For Possible Music, On gender, voice, language and identity”, Julia Eckhardt,

2018

- Jean Lacaille, Authentically Plastic : “la musique est notre garde du corps

naturel !”, PAM (Pan

African

Music), October 1st 2019

Throughout this research I investigated how female identifying artists and those from gender

minorities

can empower and emancipate themselves by alternative or DIY tools

for electronic music production.

As shown, women played an important role within the history of computing, from the very

beginning.

Further, they were also paramount for early electronic music. The way electronic music and

digital

technology field are so male-identified is a social construct, and not not a reality.

A

lot of the

technology exists because the work of FLINTA* mathematicians,

researchers or musicians, who were not

considered significant enough to be archived at the time.

Some of their works were also

overshadowed by

how we construct History: a single timeline guided by genius figures.

I prefer to look

at it as a

complex and beautiful mess where different stories and experiences intertwine. However, if

we “[avoid]

the linear, progressive, Time's(killing)-arrow mode of the Techno-Heroic”, everybody can

find their

place. This shows how important archives are, keeping track of what constructs history.

FLINTA* people

thus have to uncover and protect their own histories. More and more initiatives are being

launched to

protect the living experiences of these communities. However, some work still has to be done

to better

the representation of FLINTA* artists, and make some feel as

“valid” as their cis-gender male

counterpart as we saw in crysoma and Luisa Mei’s testimonies.

E

The lack of narratives from FLINTA* perspectives not only impacts

history, but also digital technologies

themselves. We forget or do not question where they come from or who built them. Women have

been very

important to the music industry as a labor force, and still today they work in factories

soldering

components. Moreover, the narrative carried by technologies is one of flawless performance.

Simpler,

more DIY tools might be looked down upon. I however argue that

building our own tools as FLINTA* artists

can help us escape these major technological narratives by having a better control on the

commodity

chain of our tools, and knowing exactly how they work. In fact, digital technology has been

proven to be

a great tool for the emancipation of the FLINTA* community for a long time, as I have shown

throughout

this book. They allow us to construct online communities to come together. Further, be it

through

avatars like Legacy Russell’s LuvPunk12 or Eilien’s

pitch shifting softwares,

deconstructing technology

allows us

to refigure our identities and bodies. A lot of queer artists are working on

redefining the

technologies we are working with and speculating on new imaginaries, embracing failures and

crashes

within the system as a reboot strategy.

If we embrace possible accidents, we can try or create alternative tools. Many interviewees

found that

in doing so, their music production tools felt more apt for their practice

and they

experienced a closer

connection with them. These DIY tools allow them to go in

directions they never would have achieved with

traditional softwares like Ableton. Moreover, these alternative tools can help us create our

own sound

worlds, sounds that don’t resemble others or “weird” sounds. Those “weirder” sounds carry

other

narratives, narratives that we choose to be proper to FLINTA*

artists. Think of Sara Hannies’ obsession

over her cheap bells, that are nevertheless full of meaning for her. Another example is my

interest in

noise music as a tool for deconstructing in queer beings. As music can go beyond what words

can express,

it a great way to convey parts of ourselves. Also, by using different tools, you can have a

less

readable practice that can feel both more comfortable and more emancipating, like Xaxalxe

stated. These

tools can also be more accessible, as several interviewee talked about the affordability of

alternative

softwares or DIY projects. It is important to note however, that

because of their very technical nature,

the learning curve of these alternative technologies can be heavy and it requires effort to

learn them.

But even if these tools are not always easy to learn, AFK

workshops and online get-togethers have shown

to be good ways for spreading knowledge about alternative tools. Interviewees like [MONRHEA]

stated that

by participating in workshops, they met a lot of FLINTA*

interested in Sonic Pi as well. They stated

that we should: “just sprea[d] the love and this way of approaching experimentations (…)

which is free

flowing. (…)”. Nevertheless, we have to think about creating more space dedicated

specifically for the

FLINTA* community.

As I mentioned through my anecdote about

the workshop for Tidal Cycles, if it is on a

“first come first served” basis, the majority of the participants will be cis-male-gendered.

This

results in FLINTA* artists thinking twice about registering,

fearing that the atmosphere could be too

masculine.

Even though I have shown that using DIY or alternative tools can

be a source of empowerment

and emancipation for FLINTA* artists, there is still more work we

can do to empower and enable them in

this process.

crysoma, Besançon, France

Comment avez-vous commencé à vous intéresser à la musique ?

| Solène: |

A l’école il y a plusieurs évènements par années comme des semaines de workshops et

à la fin

souvent ça se termine par un évènement, une soirée etc. Et Martha, une des

professeur.es

organisait une de ses

semaines folles et elle avait un ras-le-bol que les personnes qui mettait la musique

ou qui se

présentaient pour

des performances se soit toujours des mecs et que ça convenait à tout le monde. Il y

a un garçon

dans ma

classe qui mix un peu partout et du coup on était tout le temps ramenés à lui et ses

potes. Et

Martha le

supportait pas trop, du coup elle nous a demandé si on connaissait pas d’autres

personnes qui

faisait de la

musique, et elle nous a même demandé “Mais vous connaissez pas des gens qui vont de

la musique?

Vous voulez pas en

faire?”. Du coup on s’est dit qu’on allez essayer. Mais aussi il y avait une

émission sur Radio

Campus qui était un appel à projet ou on pouvait présenter

une création musicale ou sonore, grâce à laquelle on a aussi commencé à s’intéresser

à la

musique. |

Et comment vous est venu votre pratique de la noise ?

| S: |

On vous trouver un moyen de faire de la musique live, et à ce moment j’avais un

clavier midi

avec

Ableton mais je trouve pas ça hyper amusant, surtout à deux. Et pendant les portes

ouvertes, le

mec de la salle

informatique de l’école ramène tout le temps pleins de machines, il bidouille des

trucs et il

les laisse

aussi souvent à disposition. Donc on lui a demandé si on pouvait avoir ses machines

là. On en

parle avec

lui, et il nous dit qu’il y a une pratique qui pourrait nous plaire qui est le “no

input”. Donc

prendre

des tables de mixages et faire des feedback loops. Et nous on vient rajouter des

pédales etc.

Mais après tu

peux faire ce que tu veux.

|

Vous avez par la suite continué cette pratique, donc je me demande ce qui vous a intéressé

dans la noise

?

| Maëva: |

On a pu moduler des trucs, rajouter des pédales au no input et vraiment se faire plaisir

et

c’était vraiment trop bien de faire du son sans avoir des bases en musique, juste se

faire plaisir.

Mais après

grâce à l’école on avait accès à du matériel, si on avait été en dehors de l’école je

pense que ça

aurait été

plus dur vu que ça coute cher. On pourrait pas juste tester simplement comme ça.

|

| S: |

Aussi Christophe suivait ce qu’on faisait, un peu comme si on réalisait un de ses

rêves mais

c’était

un suivi plein de bienveillance. Il regardait un peu ce qu’on faisait comme si on

était des

scientifiques

qui faisait des expérimentations (rires). Si je revient à ce qui m’intéresse dans la

noise,

c’est vraiment une musique live dans un moment t qui

est assez difficile d’enregistrer. Je trouve qu’il y a quelque chose de très

méditatif dedans.

Comme si

t’écoutais de manière très attentive. C’est un attention qui est dure à avoir avec

la noise,

mais une

fois que tu rentres dedans c’est assez magique comme sensation.

|

| M: |

C’est pratique on la voit aussi comme un trio avec les machines. Vu que les machines

produisent du

son elles mêmes et qu’on les accompagne. |

Est ce que vous avez des personnes dans votre entourage qui font aussi de la musique ?

| S: |

Au début non, maintenant plus. C’est souvent de l’électronique. Et aussi

dans mon entourage c’est assez varié au niveau de la représentation du genre, après si je sors de ma sphère proche c’est vrai que j’ai l’impression que les personnes sont souvent de genre masculin. |

| M: |

En tout cas à l’école c’était principalement des mecs qui faisait du son.

Même que ça en fait. |

| S: |

EMais aussi quand j’étais à Genève en Erasmus à la HEAD, il y a un bon noyau de personnes qui n’était pas des mecs cis qui faisaient du son.

En tout cas dans le cours de son qui je prenais il y avait beaucoup plus de meufs que de mecs. Après c’est peut être parce qu’en école d’art il y a plus

de filles et de personnes de minorités de genre confondus que de garçons.

|

Vous créez vos propres noise boxes. Comment vous est venu l’envie de créer vos porpes instruments ?

| S: |

Maeva cherche toujours mille et une chose sur internet du coup elle est tombée sur un truc par rapport à la noise (rires).

|

| M: |